When the house lights went down on San Jose’s Center for the Performing Arts on May 17, 1984, showgoers experienced “a tempestuous noise.” Thunder clapped. Lightning struck. And out on a raging sea, a lone ship made its way out towards a magical island.

On that May night, these initial stage directions from Shakespeare’s The Tempest were lavishly performed by the San Jose Symphony Orchestra, in an extravagant joint production staged by the San Jose Repertory Theatre. Not only was the symphony involved, San Francisco’s American Conservatory Theatre contributed players as well, and funds for the night’s performance came from investment banking firm Merrill Lynch. Above the name “Shakespeare” on the marquee was the promise of a “Merrill Lynch Grand Performance.”

Yet, despite the glitz and glamor of this strangely feted Shakespearean performance, in hindsight, the most interesting thing about the night was the convergence of two of the production’s actors. In the role of the jester Trinculo was Charles Martinet, an actor who, a little over a decade later, would become the official voice of Mario in hundreds of video games from Nintendo. Playing Prince Ferdinand alongside him in the cast was the actor Michael Gough, who has likewise lent his voice work to hundreds of video games since the ‘90s.

That two of the most notable voice actors in the video game industry could be in the same San Jose Rep production together speaks clearly to the South Bay’s video game history. Too long overshadowed by the nearby giants up the peninsula and in San Francisco, San Jose and the South Bay have long played a role in nearly every part of the industry, from the programmers to the actors to the players themselves.

In fact, just before Martinet and Gough performed Shakespeare together in San Jose, another man living just a few miles away almost sank the video game industry entirely—or so the legend goes.

PHONE HOME

Long before Super Mario Brothers, Minecraft and Fortnite, there was Computer Space, the first commercial arcade machine ever built. Loud and futuristic, 1971’s Computer Space tasked players with commanding a hurtling spaceship while avoiding aliens and enemy rockets—and it was manufactured in Mountain View by the tragically named Nutting Associates.

Though Computer Space was far from a runaway hit, the following year, the game’s creators formed a new company called Atari, and found their runaway hit with the table-tennis simulator Pong. The first cabinet of that game was beta tested by the public at 157 W. El Camino in Sunnyvale, current home of comedy club Rooster T. Feathers.

But in the years 1983-85, the video game industry went through an unprecedented crash, losing billions of dollars almost overnight. In Japan, this crash is known as “Atari Shock.” Though there were many factors at play at the time, the traditional narrative lays the blame for the industry crash on exactly one game: E.T.

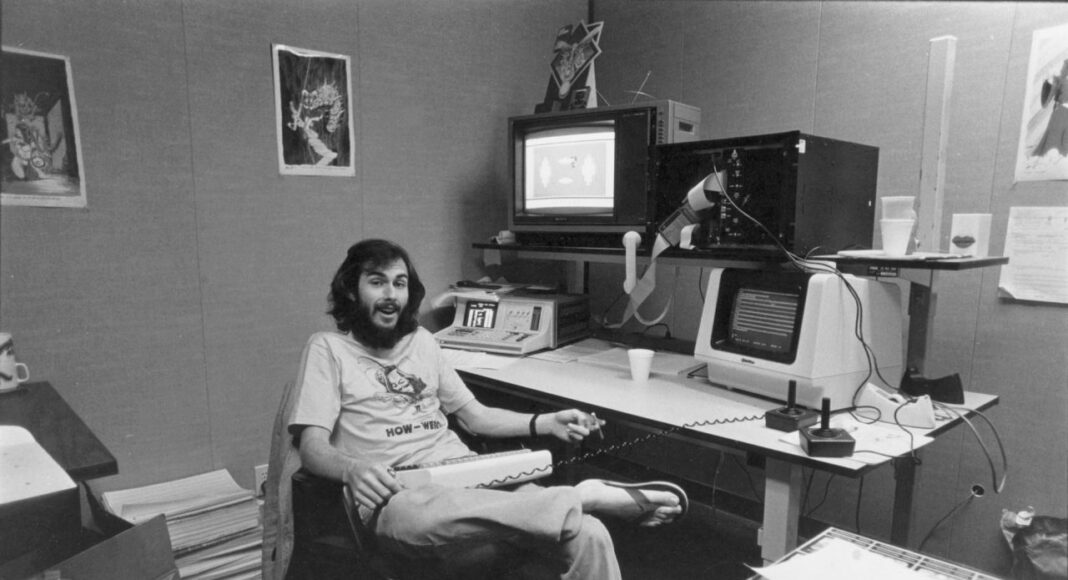

“I did E.T. while I lived in Campbell,” says Howard Scott Warshaw, the game’s lone programmer.

As an official tie-in with the biggest movie of 1982, E.T. was set to be a smash hit. Instead, it was the exact opposite, confounding gamers with its opaque gameplay, confusing layout and constant onset of sudden death. Famously, Atari wound up burying a large quantity of unsold cartridges in the Alamogordo desert in New Mexico—along with other industrial waste.

In his recent memoir Once Upon Atari: How I Made History By Killing An Industry, Warshaw recalls how in July of 1982, Atari head Ray Kazar called and asked if he could turn in a completed E.T. video game by September 1st—a total development time of only five weeks.

“Without missing a beat, I sa[id], ‘Absolutely I can,’” he writes.

Prior to E.T., Warshaw had programmed Atari’s official Raiders of the Lost Ark video game. Before that, the iconoclastic programmer had been assigned to make an Atari version of the arcade game Star Castle. Instead, he created a new one from scratch, a bizarre action game called Yar’s Revenge, in which players control humanoid flies called “Yars,” and attempt to chew up and spit out an evil alien ship.

“Yars is a really good window into my psyche,” Warshaw says. “Visually, audio-wise, all of these things, Yar’s Revenge is intrusive. It’s about doing something different and something that’s difficult to ignore. I wanted to do something that demanded people’s attention.”

Upon the success of his first two games, it seemed that E.T. was set to be Warshaw’s legacy—and in many ways it was. E.T. is regarded as one of the most consequential games of all time, not only nearly tanking an industry, but “practically set[ting] the standard that all video games based on movies will suck,” according to GamePro.

Today, opinion has softened on that latter point, with many now saying the game’s impressionistic imagery and proto-open-world design were ahead of their time and technology. Warshaw, for his part, says that the impossible five week deadline accounts for many of the game’s, let’s say, quirks (for comparison, most other Atari games took at least six months to develop).

As for the industry crash of ‘83, Warshaw sees many factors at play bigger than one little game. Within Atari, there was dissension and mismanagement. And on a wider scale, there was the generally tumultuous early stage of the industry.

“To financiers and investors, it looked like a fad, and a lot of people on the investment side saw it as a fad,” Warshaw says. “But the people making video games knew there was no way that this was a fad. This was a new media.”

After leaving Atari, Warshaw never stopped engaging his creative impulses. He wrote a series of books on subjects ranging from college life to psychology to gaming, and in 2005 he made a documentary on San Francisco’s BDSM scene which has since been used in college sexuality courses. These days, he practices psychology, calling himself the Silicon Valley Psychologist.

However, little compares to the strange few years he spent dedicating his life to video games—and then almost destroying them altogether.

“Atari was the fastest growing business in American history…and then became the fastest falling company in history,” he says. “It was like, ‘Let’s build the biggest balloon that goes up the fastest. It’ll go to a certain height and then it’ll pop.’ That was Atari.”

FRAT CRAFT

In January, former employees of Santa Monica game developer Activision/Blizzard filed a class action lawsuit against the company, alleging long-standing issues of gender-based discrimination, sexual harrassment and abuse at the gaming giant.

The Activision/Blizzard suit paints a grim portrait of the gaming industry. In it, former employees describe an environment where harrassment and misogyny were common, and one developer’s room obtained the nickname the “Cosby Suite” for his habit of mistreating women. Said developer responded to the nickname by installing a portrait of the disgraced comedian/abuser in the room and regularly posing with it.

Sadly, this thread also connects back to the South Bay’s gaming history. Activision originally began as an Atari spinoff, created by a group of developers who all quit over lack of royalties and recognition. In the process, they created the first-ever third-party video game developer.

While all four of Activision’s founders left the company back in the 1980s, documentation of similar issues at Atari are not hard to find. Despite being at the top of the industry, Atari only had three women engineers developing cartridges, and only one working in the coin-op division. When, in 2018, the Game Developers Conference announced they would be honoring founder Nolan Bushnell with a Pioneer Award, numerous stories of sexual harrasment and discrimination at the company emerged, including explicit comments, literal objectification (shapely arcade machines were named after certain female employees) and attempts to persuade women employees into a hot tub.

In his memoir, Warshaw also recalls how Atari developers would often drive to Reno on what they called “Scumbagathons,” which were exactly what the name implies.

Now a psychologist, Warshaw says you can always find the mark of someone’s worldview in the art they create.

“Everybody signs their work,” he says. “Everything that you look at that someone produced, it’s going to contain a lot of information about that person, if you know how to read it.”

Perhaps it should be no mystery then why there have been such persistent issues of misogyny in gaming, as recently exemplified by the #GamerGate harassment campaign from 2013-14: if toxic males are creating the worlds young people are experiencing, and everyone signs their work, then those young people will likely experience the world through the eyes of a toxic male.

Thankfully, there have also always been great women working hard for gaming throughout the South Bay, including programmers, writers, artists, and every other part of the industry (personally, an aunt of mine was a developer for years at Sega, just up the peninsula).

On a more heartening note, Carol Shaw, one of Atari’s four women developers and the creator of the classic River Raid, gave an interview with Vintage Computing and Gaming in 2011. When asked if sexual harassment had been an issue during her time in the industry, she answered: “No, I never really ran into that. It didn’t seem to be a problem.”

VOCAL SUPPORT

Video games have come a long way since Atari, but one guy in particular has been jumping along from platform to platform for almost the entire ride: a little mustachioed plumber in overalls named Mario.

Within the world of video games, few voices are more famous than the sprightly yip, ya-hoo and here we go of Mario. Yet the origins of that voice have rarely been told. Though he is said to be from Brooklyn, and first came to life on a computer screen in Tokyo, surprisingly, Mario’s vocals were first performed right here in San Jose.

Charles Martinet, the voice of Mario since 1996’s Super Mario 64, was born in San Jose and spent his formative years in Cupertino. As he told Metro in 2018, he based his voice for the timeless hero on his performance of Gremio in a 1983 San Jose Repertory Theatre production of the Taming of Shrew.

But Martinet is far from the only video game voice to come from San Jose. Anyone who has picked up a controller, mouse—or even watched cartoons—in the last 35 years has likely heard the voice of Michael Gough.

“Stay a while and listen,” Gough intones in the voice of Diablo sorcerer Deckard Caine.

Over the last three decades, Gough has performed roles in more than 140 games, vocalizing in everything from Blizzard’s famous dungeon-crawling Diablo series to psychedelic new-wave nightmare Killer 7 to open-world fantasy epic Skyrim, in which he voiced 63 different characters, including the apocalyptic zealot Heimskr.

Gough’s most famous role, however, is something a little more green.

“One of the nice gigs I’ve had is that I was the official backup voice for Shrek,” he says.

At this point, Gough has voiced the inexplicably Scottish ogre in nearly every project that “Mike Myers wasn’t available to do or they couldn’t afford him or whatever,” including six different video games, advertisements for both McDonalds and Sierra Mist, and a Shrek themed attraction located along the River Thames in London.

Gough got started acting on something of a whim, auditioning for a student one-act just before he graduated from UC Santa Barbara with a degree in English.

“I had always enjoyed reading out loud, just kind of sitting around in my room doing voices. I thought it would be fun before I left school,” he says. “So I went and auditioned and this one gal picked me to be in her play. We’re actually still really good friends.”

Gough’s first major role as a voice actor was in the late ‘80s Winnie the Pooh cartoon, playing the hard-working, whistley-toothed Gopher. Gough describes voice acting—particularly for video games—as being like “vocal green screen acting.”

“You kind of have to be a quick study,” he says. “Often, you’re just doing it yourself. Usually you’re not acting with anybody else. You’re given the context and then use your imagination. Hopefully you’re being guided well by the director.”

There was, however, that one time Gough got to work in person with another famous voice actor.

Though he didn’t start acting until leaving the Bay Area for school in Santa Barbara, his first paid gig—the gig that would eventually get him into SAG—was that massive San Jose Repertory Theatre production of Shakespeare’s The Tempest, alongside none other than the voice of Mario.

“This was long before either of us had any inkling of doing voice stuff for video games,” he says. “But we were in that show together.”

A review from the time published in the Mercury News describes the Rep’s Tempest as a qualified success. What complaints they have largely stem from how “many key elements” of the production were turned over to non-Rep workers, including the play’s director and main actor. However, the article does mention both Martinet and Gough for the strength of their performances: Martinet for his “funky, hilarious Trinculo,” and Gough for his “matinee idol” looks that “make the swooning with Mayock seem especially romantic.”

FAST AND PHILANTHROPIC

Watson Tungjunyatham stills remembers the first time he saw a MaiMai video game. At the time, he was at an arcade in Japan, where he was studying abroad. There, across the room, stood a large, glowing box with a circular screen that sort of looked like a washing machine.

“It was such an eyesore because of how huge and flashy it was. I was like, ‘What is this game?’”

The game was MaiMai GReeN, the third in Sega’s rhythm series. In it, players slap a ring of buttons surrounding the circular screen to pop bubbles and stars and connect glowing trails from one side of the screen to the other—all to the beat of some of Sega’s most memorable songs.

Tungjunyatham was immediately drawn in, and not just because the game was “huge and flashy.” By that time, he was already well on his way to becoming a master of the rhythm game form.

“I was really into rhythm games,” he says. “My friends all clearly knew that. They were like, ‘Oh, you’re the kid that can play DDR!’”

This past July, the young Sunnyvale-based software engineer also known by gamer tag Starrodkirby86 turned his rhythm game skills into an act of humanitarianism. In a performance lasting a little over an hour, Tungjunyatham helped raise $220,000 for Doctors Without Borders. The money was contributed by Twitch viewers excited to see him do what he does best: play MaiMai to near perfection.

Tungjunyatham’s performance came as part of the video game speedrunning festival Summer Games Done Quick. Held yearly over Twitch (and directed by a former San Jose resident), the event gathers video game fans and players together to experience some of the most incredible video game performances possible—all for charity. In total, this year’s event raised close to $3 million for Medicines San Frontiers/Doctors Without Borders.

However, few performances were as impressive as Tungjunyatham’s. For it to even become available, viewers collectively contributed $120,000 during an earlier part of the festival. By the last song, the speed and precision at which the gamer’s hands were flying is difficult to believe. Between rounds, he paused to speak to the announcers and give his shoulders a break.

“It was only more recently in the past couple of years that I realized that MaiMai wasn’t just this kind of dance game, but instead more of a physically demanding game that actually has a really high skill ceiling that’s not easily perceived,” he says.

To help break through that ceiling, Tungyunyatham befriended the private owner of a MaiMai machine at a Fanime convention in San Jose. Before long, they were regularly hanging out in the garage, jamming along to Sega.

“I made quick friends with this fellow, and I found that he lived about 5 minutes away from me. It was a delightful coincidence,” he says. “I got to come over a lot and actually practice the game and, I guess, kind of get really good at it.”

Whether programming them, acting in them or playing them to perfection, getting really good at video games is a thread that runs through the culture of the South Bay.

“The Bay Area has a really good community of people who want to positively support each other,” Tungjunyatham says. “If it weren’t for these spaces and conventions like Fanime, I probably would have driven myself a little crazy while here in Silicon Valley.”

FOUND HOME

For the gaming community, the South Bay has always offered a distinct and robust homebase—the kind of place that provides community to players like Tungjunyatham, and allows future industry stars like Martinet and Gough to develop their chops. Warshaw, who went to school in New Orleans and spent eighteen years in New Jersey, says he felt it as soon as he set foot in the Valley.

“The first time I arrived, I had this feeling that I was home,” he says. “When I got off the plane and started walking toward the terminal, I had this overwhelming feeling of ‘This is my place. This is where I need to be.’”

Not that everyone agreed with him, after they heard him talk.

“But then when I’d meet people, the first thing they’d say to me is, ‘You’re from the East Coast, huh?’”