Jonah Peretti’s office has two glass walls, two white walls and no decoration except for a giant, multicolored rectangle, with blue and violet hues fading upward and coalescing into a tight little rainbow wheel at the top. The artist Cory Archangel, a friend of Peretti’s, makes these “gradient paintings” with one click in Photoshop, blows them up and sells them for lots of money, Peretti said. It is, in his words, “kind of a joke.”

Peretti, 38, a navy-eyed, wavy-haired nerd-king with a machine-gun giggle, was a cofounder of the Huffington Post before he moved on to other things. He likes these gradient paintings a lot. His Twitter page is also a gradient. Peretti, a career mischief maker with a “great, sort of trollish sense of humor,” as one former employee put it, likes jokes best when they’re subversive. He’s infamous for arguing that Mormonism is superior to Judaism because of its growing numbers, a shtick he uses in presentations. As a grad student at MIT in 2001, he ordered a pair of custom Nikes embroidered with the word “sweatshop,” extracting a series of awkward emails from an unlucky customer service rep. He forwarded the emails to a few friends, who forwarded them to their friends, and so on. Literally millions of people have read them.

“I didn’t really know anything about the sweatshop issue, but I ended up on the Today show with Nike’s head of global PR, debating sweatshop labor,” said Peretti, at the shiny headquarters of his company, BuzzFeed, a website that has spent the past three years cornering the market in items along the lines of “The 30 Best Taco-Related Crimes Ever” and “Sexist ’60s Coffee Ads.”

In December, BuzzFeed announced a surprise move that furrowed brows throughout the media industry. The site was bringing on a news reporting team and had poached Politico superstar Ben Smith to run it. “It was, to many, a bit as though Jane Lynch, at the height of her popularity on Glee, had announced that she was leaving the cast to participate in a season of Celebrity Apprentice,” wrote Tom McGeveran at Capital New York.

Smith was impressed by Peretti, who battered him with visions of BuzzFeed 2.0: serious news scoops vying for attention with the web gags. It would be a site that resembled the dizzying editorial mix readers find in their Twitter and Facebook feeds, a sticky alternative to all those tired “commodity news” sites, with their comprehensive self-seriousness and dryly logical architecture.

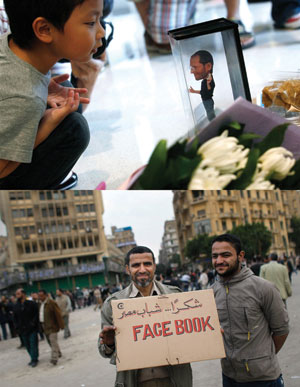

Reporters often try to feed readers their vitamins; as journalism professors are fond of saying, “Don’t give ’em what they want. Give ’em what’s good for ’em!” The new BuzzFeed wants to give ’em both. “The Facebook News Feed and your Twitter stream are filled with fun items, personal updates and news,” Peretti wrote in an email. “As social sites become the way people discover content, readers expect a very diverse mix. News on BuzzFeed is part of a much larger shift in the media industry toward social content. The shift has already happened, but we are just starting to understand what it means.”

Smith scoffed at the notion of editing such a beast, but he was intrigued enough to recount the conversation later to his wife, who asked him: Wait, why don’t you want to do this? After a bit more waffling, he did—largely because he was impressed with Peretti. “He actually has his arms around the media ecosystem, how information is distributed, at a level of sophistication that is hard to fake,” noted Smith.

Peretti is personable and energetic. He tends to reposition dramatically when the conversation turns to a new idea: from excited, with his hands behind his head, to thoughtful, with his arms tightly crossed, to relaxed, propping himself up with one arm as he absentmindedly scratches an ankle.

The man David Carr described as a “viral marketing hotdog” is an exalted member of the viral media mafia, the group of Internet noisemakers that includes people like video entertainer Ze Frank, Uberblogger Jason Kottke, virtual stuntman Alex Blagg, Reddit cofounder Alexis Ohanian, Texts From Last Night co-founder Lauren Leto and Chris “Moot” Poole, the god of the greatest meme factory of all, 4chan, many of whom mingle incestuously through hubs like the MIT Media Lab, the Eyebeam Art and Technology Center and the Free Art and Technology Lab.

Peretti’s sudden fame with the Nike sweatshop emails was an accident. But he wondered if it would it be possible to make viral happen, again and again.

Perhaps you remember BlackPeopleLoveUs.com, the website of a white couple who protested too much? Or maybe the Rejection Line, a fake phone number that let suitors down easy with a soothing voicemail? Both were weekend projects Peretti cooked up with his sister Chelsea, a standup comedian and writer for Parks and Recreation—experiments designed to see if he could replicate the viral effect.

“When we were doing our early joint projects, people kept asking us if we were making money off our ideas,” Chelsea Peretti wrote in an email. “We kept having to tell people no.” She added, “It feels great to know how far we’ve come and that now we are both millionaires. And by ‘both,’ I mean just my brother.”

Peretti angled his expertise into consulting jobs and teaching gigs at NYU’s ITP lab and the Parsons School of Design, and the Huffington Post, where he invented what he called the “mullet strategy”—smooth, professional content on the front page, with messy, user-generated stuff buried in back—honed the site’s SEO and created FundRace.org, a searchable database of campaign contributions.

In 2003—which, on the timeline of Internet memes, would be four years before LOLcats, five years before Stuff White People Like, and seven years before People of Walmart—Peretti opened a class on Contagious Media by drawing two curves on the board: a spike followed by a plateau, vs. a spike followed by a drop. Useful technology tends to spike, then flatten out, but it holds because it’s useful, he told the students.

Viral media has an even faster growth rate but plummets into obscurity after it peaks (although Black People Love Us is still in the Top 10 Google results for “black people”). “You got your kicks, and you’re off to the next thing,” explained Paul Berry, a former student Peretti eventually recruited to be CTO of Huffington Post. (Berry recently left to launch a viral media incubator, in which Peretti is an investor.)

Sketching graphs and tracking email forwards isn’t as fun as, say, clicking on BarackObamaIsYourNewBicycle. But intentional virality takes work. BuzzFeed’s white-walled, bullpen-style office is quiet, with 20-somethings hunched over in office chairs, pacified by headphones, clicking and clicking. We tried to peek—what were they looking at? Photoshop. A website we didn’t recognize. Was that Facebook? These editors employ the spaghetti-to-wall strategy, posting a wide variety of items rapidly throughout the day while watching BuzzFeed’s internal metrics to see what hits.

The site has become adept at repackaging content in creative ways. Perhaps the best way to present the contrasts between presidential candidates, for instance, is not an article but 20 captioned photos. BuzzFeed employee Andrew Kacyznski, a 22-year-old student who seems destined for The Daily Show due to his compulsive C-SPAN trawling, is making an art of telling stories through video mashups.

That said, the goal isn’t for everything on the site to go viral. “You could have that as your goal, I guess,” Peretti said, “if you like to be a delusionally positive thinker.”

It wasn’t too much to ask of his class in 2003, though, who were told to build viral websites. Whoever got the most traffic got an A. “The point of this class is not useful technology,” Peretti told his students.

Berry, who was in that class, teamed up with another student to build a website called Dog Island, a paradise for canines whose fictional creator, “Linda Reyes,” believed passionately that dogs should be removed from Manhattan for their own well-being. The site had an elaborate backstory suggesting Chinese dog meat processors might be involved, and included a link to the Dog Exportation Act on a fake version of the local legislative website.

Hours after Berry put up a few posts for Dog Island apartments on Craigslist, it went viral. Craig Newmark, overwhelmed with inquiries and furious emails, sent a confused note two days later.

Dog Island got the most hits in the class, something like six million page views. One other project got close: WhatIsVictoriasSecret.com, which was just pictures of girls vomiting.

The failures were as instructive as the successes. Peretti fondly recalled “gangster henna,” a fake website about hard-core prison tattoos created with henna, which flopped.

Why did Dog Island go viral, while gangster henna did not? There are no rules, but there are guidelines. “Most things aren’t viral” is one of Peretti’s catch phrases. The thing can’t be too complicated, and it almost always has to be original. “Oftentimes, when people see something that was viral, they will copy it, and then that thing will be less viral,” he said (like those books that are made from Tumblrs?).

Novelty is viral; humor is often viral, as are things that inspire awe or a strong emotion other than sadness. “For the most part, if something is a total bummer, people don’t share it,” he said. “You don’t want to upset all your friends. I’ve met activists before who come to me and say, ‘Help me make my campaigns viral.’ And then I’ll say, ‘OK, let me see what you’re working on,’ and then their campaign is literally pictures of starving children that are literally about to die.”

A lot of Peretti’s strategy has to do with appealing to people’s vanity: You want them to feel good about themselves for discovering a thing and proud to be the first one to show it to their friends. That means that some things aren’t “shareable”—sex tapes, nasty stories and celebrity dross, for instance, which Peretti calls “guilty pleasures.”

Those tend to be spread by email and word of mouth, which are much less contagious than social media.

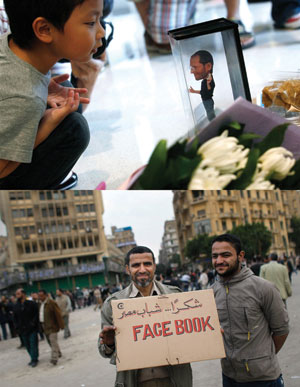

Nostalgia does well, though—”25 Foods You’ll Never Be Able to Eat Again” was a hit. But a wacky premise isn’t as key an ingredient as one might think; the all-time most viral post on BuzzFeed is “The 45 Most Powerful Images of 2011,” which might offer a clue about the motivation behind Peretti’s shift into straight news.

BuzzFeed is more than a blog, though. It’s a testing-ground for technology that monitors the web, scanning for content that is about to blow up, using a proprietary algorithm that watches the type of traffic heading into a story, photo series or video and acts as an early-warning system when something has the potential for exponential popularity.

At that moment, BuzzFeed flows the item into a rotation of prominent positions on the site, helping to catalyze its rise. It does the same thing for advertisers, making millions of dollars in revenue a year, the company says, by running sponsored content from brands like Coke, Kraft and Disney, and supplying its sponsors with a dashboard and metrics.

There’s something chilling about all this—the systematic monetization of the Internet’s forest of delights in the service of corporate marketers. It all used to be so innocent: a hallucinating hippie makes an unintentionally funny video of a double rainbow and uploads it to YouTube, where it lies, a diamond in the rough, until it’s stumbled upon by an Internet explorer. Serendipity is the great magic of the Internet; distilling it into a formula seems wrong.

Then again, it might be just what the media business needs. BuzzFeed recently announced a $15.5 million round of outside funding, is up to about 70 employees, and Smith is hiring reporters.

We tried to get Peretti to give us a peek at the crystal ball. Why news? Why now? Are memes over—just a phase we all went through, like a collective adolescence of the Internet?

“Novelty items, memes and cute kittens all have a bright future on the social web,” Peretti reassured us, “but increasingly they will have to share the stage with substantive content, original reporting and breaking news.”

In early January, BuzzFeed broke the news of John McCain’s endorsement of Mitt Romney, forcing CNN to admit “news of the endorsement was first reported by BuzzFeed Politics.” (LOL.) BuzzFeed’s arrival has resulted in some grumbling from political hacks, but it’s largely been greeted with optimism. Media critic Jack Shafer, now at Reuters, hailed BuzzFeed in a column as ‘the daily newspaper reborn again.’

Of course, what BuzzFeed is doing—original reporting of serious issues alongside aggregation, listicles, snark and video mashups—is not so new. The Huffington Post has a similar mix, as does Gawker and everyone. A recent headline on The Atlantic‘s website read: “Science Can Neither Explain Nor Deny the Awesomeness of This Sledding Crow.”

“They’re very aggressively carving out parts of political news that has even a faster metabolism than Politico,” Shafer marveled of the politics team. “I imagine the entire staff is heavily dosed on Adderall.”

He’s a particular fan of mashup wizard Andrew Kacyzinski, he added. “That kid is the greatest thing since garlic toast.”

Reprinted from The New York Observer