Although today’s political discourse has descended to levels usually associated only with sump pumps, our forebears were hardly models of rhetorical rectitude either. Mitt Romney, who seems unduly sensitive for someone named after a piece of sporting equipment (now I’m doing it, too), might consider the brouhaha over his tax returns deeply unfair, but he hasn’t had to endure the vicious visual taunting dished out to another 1 percenter, King Louis-Philippe I of France, by Honore Daumier and his collaborators at a satirical Parisian rag known as La Caricature.

“When Artists Attack the King”, a new exhibit at Stanford’s Cantor Arts Center, offers some prime examples of scathing ridicule by cartoonists wielding acid-tipped quill pens. No aspect of their targets’ physiognomy was considered off-limits. The king, a hefty fellow, was depicted with the bottom-heavy form of a rotting pear. He and his ministers were routinely shown carrying out heinous crimes. For their troubles, the artists and their fearless publisher spent time in jail during various censorship crusades.

The period covered is a brief one, from 1830 to 1835. King Louis-Philippe came to power in the wake of the July Revolution, which toppled Charles X. Supposedly more liberal, Louis-Philippe promised to chart a course between royalism and resistance. The honeymoon proved to be short-lived, and the king’s “reforms” looked increasingly like a stealth movement to bolster a new elite: the haute bourgeoisie. Early on, J.J. Grandville mocked the king’s initiative with a cartoon showing Louis-Philippe hoisting a bare-bottomed baby (the so-called “middle way”) while Mother Freedom suffers from a severe case of post-partum depression.

Leading the liberal charge was La Caricature, a journal of invective that combined words and engravings to powerful effect. Charles Philipon, a lithographer and publisher, turned loose the young Daumier and other artists to produce prints that consistently evoked the king’s ire. One can sympathize, at a distance, with the king’s feelings when he saw Daumier’s lithograph of his daughter as an obese prostitute surrounded by ill-gotten gold. In another print, Daumier transforms the king himself into a grotesque Buddha figure dripping with fat rolls. Most frequently, La Caricature equated the king’s shapeless body to the slang meaning of pear (la poire): “fat head,” “idiot,” etc. In one elaborate image, Auguste Desperret turns the king into a pear-shaped fortress under siege by the press, firing projectile-shaped journals at his highness.

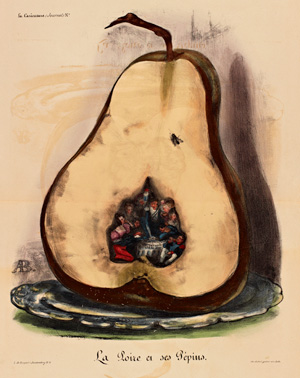

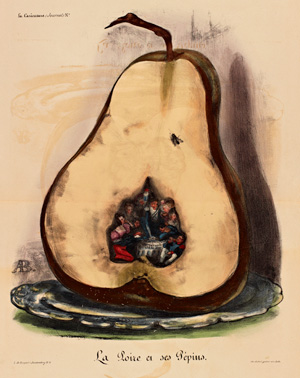

Sometimes, the magazine used an actual pear as a handy symbol of royal corruption, as in Auguste Bouquet’s “The Pear and Its Seeds.” Inside a delicately colored half-pear, government ministers connive, protected by the king’s pulp.

More directly, and trenchantly, Daumier’s Travel Across the Attentive Population presents the king from behind, his thighs bulging out of his saddle, as he rides across a landscape full of naked corpses, while flocks of vultures prepare to feast. Daumier’s powerful Rue Transnonain, le 15 April 1834 zeroes in with documentary attention to detail on the bodies of a family murdered in its home by the king’s soldiers. This piece has the impact of one of Goya’s Disasters of War series.

In an almost elegiac mood, Daumier’s Lower the Curtain, the Farce Is Over finds the king, rotund as ever, sporting a clown’s checkered suit and wide ruffled collar. Tipping his comic chapeau, he points to the populace that has been his captive audience for too long. This print is distinguished by its graphic starkness and the use of heavy black shadow framing the king.

Daumier dominates the show, but some his fellow caricaturists demonstrate a common glee in skewering the powerful and pompous. Bouquet draws one of the king’s henchman with a nose like a saw that he uses to behead enemies of the state. Benjamin Roubaud traffics in blasphemy with Revolutionary Stage, dropping the king and his ministers into a Last Supper tableaux—with a pear, naturally, for the centerpiece.

La Caricature wasn’t above some revolutionary hagiography. Daumier’s Don’t You Meddle With ItI! contrasts a sturdy, heroic printer, dressed in simple garb, standing tall against the crouching, craven authorities who would dare attempt to silence him. Even better is the artist’s So, You Want to Meddle With the Press!!, which finds a printer squashing the king’s head under the heavy iron platen of his press—a timeless statement of principle for newspapers, if they are willing to pay the price.

Eventually, the price became too high as La Caricature was hounded out of business in 1835. Cheekily, Philipon set the type for the final issue in the shape of a pear—and then went on start Le Charivari, a satirical newspaper aimed at bourgeois life in general, rather than politics specifically. It published all the way to 1937.

Runs through Nov. 11