Penny Speight spent much of her childhood trying to find a place to fit in.

Raised in her grandmother’s home in Stockton, she spent little time outside of school, church and with her family. “I wouldn’t say there were a ton of black people,” she says of her hometown, “but I was raised by my black family and I was always around them.” Her life at home had a soundtrack—grandma approved of Whitney Houston tracks “I Believe in You and Me” and “Joy to the World,” while Snoop Dogg, Outkast, Fugees and BET videos were off-limits. The sounds were accompanied by the familiar smell of collard greens, fried chicken and candied yams. But life outside the home wasn’t always so easy.

Speight is bi-racial, both black and white, and despite the fact that she identifies herself as African American, she found that as she was growing up, her classmates didn’t see her as such, based on the fact that she had lighter skin. In high school, she moved to Clearlake, a town with few black people. College would be different, where Speight, 21, anticipated more diversity and a larger black population at San Jose State University. “I was overwhelmed with all the people and all the things you could do, because Clearlake is very small,” Speight says. “When I came to San Jose State, I became more open-minded. It was like a whole new world.”

What she didn’t encounter, to her surprise, was a strong African American presence, on campus or in the city.

“I was hoping there were going to be more black people here, because in Clearlake there were like five black people,” Speight says. “I was disappointed with the lack of community. We are so small, we should be more united, but we’re not.”

Santa Clara County is one of the most diverse areas in the country, and yet the black population has remained remarkably low over the last half-century and is even shrinking.

According to the most recent county census, the white population peaked in Santa Clara County in 1960 at 96.8 percent. According to the 2010 census, Caucasians accounted for 47 percent. (It wasn’t until the ’70s when Latino/Hispanic became its own category.) Over time, though, the Asian and Latino communities have substantially increased.

The Asian population was below 3 percent in the ’50s and ’60s, but grew to nearly 8 percent in the ’80s, 17.5 percent in the ’90s and 32 percent in 2010. The Latino community has experienced similar growth, going from 12.2 percent in 1950 to 20.5 percent in 1980 and 26.9 percent in 2010.

Meanwhile, the black population has remained surprisingly low, from less than 1 percent in the ’50s and ’60s to 1.7 percent in the ’70s. African Americans accounted for 3.7 percent of the population in the ’90s, but by 2010, that percentage dropped back down to 2.6, or about 46,428 people.

Steven Millner, an African American studies professor at San Jose State, has lived in Santa Clara County since 1968, and over the years he has seen the black population’s ebbs and flows.

Many African Americans moved to San Jose in the 1940s and 1950s for job opportunities in the cannery business, Millner notes. Cannery jobs, located near the black communities, were a sufficient means of income at the time. But when the canneries closed, Silicon Valley’s working class also left the area.

In the 1960s, Millner says, technology firms recruited black engineers, making San Jose one of the country’s most educated African American clusters. But many of these engineers have since retired and migrated out of the area.

“In the last 10 years, it’s been a flow away from Santa Clara County,” Millner says, pointing out that the African American children of those who prospered in the ’60s have dispersed throughout California and the nation.

“A lot of times the children of black professionals go to historically black colleges,” Millner says, listing several prominent schools in the South.

Meanwhile, San Jose has grown and attracted a diverse collage of cultures with the growth of Silicon Valley’s technology industry, according to Tomas Jimenez, a sociology professor at Stanford University.

“In this area there’s a huge demand for people in the science, technology and math industries, and so we draw internationally for a high skilled workforce,” Jimenez said.

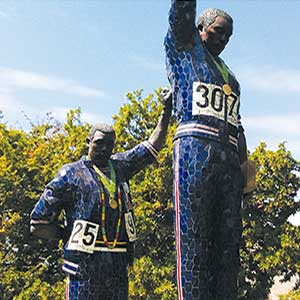

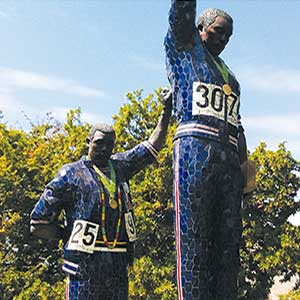

In 1968, San Jose State students and Olympic sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos made civil rights history, raising their black-gloved fists as a salute to black power during the medal ceremony at the 1968 games in Mexico City.

While a statue of the two men stands on campus to commemorate the iconic moment, there is little connection to the students of today, says Reverend Jethroe Moore, president of the NAACP chapter in San Jose.

“San Jose State was the birthplace of a great civil rights movement, but San Jose does not teach that, advertise that or promote the fact that this was started by blacks,” he says. “They tend to hide it, and black people tend to be one thing that this county hides.”

Moore adds that the minimum wage ordinance in San Jose began as a campaign started by an African American student at San Jose State, a fact that is often overlooked.

In the ’60s and ’70s, employment opportunities in the manufacturing industry attracted black workers, but “there were choices and decisions made that hindered the growth of the black community,” Moore says. He says that part of Northern California’s institutional racism has been keeping those who live in other cities from getting to San Jose. “We are one of the biggest cities in the nation but there isn’t a black community,” Moore says. “BART was never extended to San Jose. Why?”

Answering his own question, Moore claims that BART was originally designed in such a way as to lessen opportunities for people of color or low income. He notes that at the time there was economic prosperity in Silicon Valley and a large tax base to pay for the extension of BART, but the rail line wasn’t expanded. With many African Americans living in the East Bay, transportation impediments made it harder to commute.

Rick Callender, vice president of the California and Hawaii NAACP, adds that institutional racism can be as subtle as established cultures hiring those with similar backgrounds.

“If jobs weren’t there and your community isn’t there, then you go where jobs and your community are,” Callender says.

Judge LaDoris Cordell, who now serves as San Jose’s independent police auditor, has lived in Santa Clara County since 1971, when she started attending Stanford University. She has seen housing prices skyrocket since that time, which especially affects lower-income families, such as many African Americans and Latinos. “I see a great divide getting bigger and bigger between the haves and have-nots,” Cordell says. “I’m not happy about what I’m seeing…. My daughters don’t live here because they can’t afford it. They would like to come back, but they can’t.

“How do you break the cycle? I don’t know.”

Although the African American community continues to shrink, those emigrating from Africa to Silicon Valley seem to have increased. “Those who are African American tend to be African, and their emergence in this area has been one of the more fascinating developments,” Millner says. “They have refugee status, which is recognition that they come from a war-torn background as opposed to waiting 10 to 12 years for an immigrant visa.” But as more people from Eritrea, Ethiopia and Nigeria come here, a shift is taking place in the black community.

Although first- and second-generation African families may appear to be the same as those whose ancestors were brought over on slave ships, their experiences tend to differ, Millner says. “There is a divide between the black community and Africans,” he says. “If there is going to be black growth, it’s going to come from those groups.”

As for Speight, she has not given up on San Jose’s potential to be an attractive place for young African Americans.

“Overall my experience has been good,” she says. “I’ve met a ton of great people, but I really envision us being closer together and uniting for a common goal: equality. I see us doing great things here, but we have to come together.”