home | metro silicon valley index | the arts | books | review

2006 Holiday Gift Guide:

Hall of Shame Gift Guide | CD box sets | Book gifts | Politically incorrect DVDs | Holiday movie preview | Holiday event list

Golden States

The season's gift books with a California twist

By Michael S. Gant

IN Permissions: A Survival Guide (University of Chicago; 188 pages; $15 paper), Susan M. Bielstein asks, "Will there always be art books?" Once upon a time, the answer was a given; now, thanks to the financial demands of copyright holders (artists' estates, photographers and museums), Bielstein writes, "This segment of the publishing industry has become so severely compromised that the art monograph is now seriously endangered and could very well outpace the silvery minnow in its rush to extinction."

Emboldened by laws that protect works for the life of the creator plus 70 years and by loopholes in the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, anyone with the legal muscle to assert a copyright (including James Joyce's litigious grandson, who is busy stifling Joyce studies) can hold publishing projects hostage. Meanwhile, the public domain and the principle of fair use beat a sullen retreat.

I wouldn't recommend Bielstein's book as a gift (unless you have an aspiring intellectual-property attorney on your list), but I certainly advise taking advantage of the coffee-table specials that publishers (especially university presses) are still able to justify on their bottom lines, because some day soon we may be buying art books that are all text and no pictures—and that's no present at all.

I also like to think and buy locally; so this year's list focuses on California vistas and visionary artists. Be sure to check the shelves of a neighborhood bookstore—there's no substitute for the pleasures of browsing—before turning to Amazon.

Valley of Delights

No, not Santa Clara but Yosemite. The season's most impressive art book, Yosemite (University of California; 232 pages; $65 cloth, $34.95 paper), is aptly subtitled Art of an American Icon. The storied national park has attracted artists since the late 1850s. Landscape painters like Thomas Moran, Thomas Hill, William Keith and Albert Bierstadt created mega-canvases that introduced the public to the wonders of a new Eden on the West Coast. Intrepid photographers Carleton Watkins, Eadweard Muybridge and Charles Weed flooded the market with prints and stereo-views of Half Dome, El Capitan and Bridal Falls, until Yosemite became as much an aesthetic concept as an actual place.

The 20th-century image of Yosemite was dominated by the pristine, unpeopled granitescapes of Ansel Adams, until a new generation of ironists like Ted Orland and Rondal Partridge started photographing the tourists and cars that threaten the fragile ecosystem.

In addition to the spectacular illustrations—the chapter on the early photographers includes some breath-taking panoramas—Yosemite boasts some unusually astute and readable analyses by a half-dozen guest scholars. Frederic Church, Winslow Homer and Thomas Moran: Tourism and the American Landscape (Bulfinch; 192 pages; $50 cloth) expands the discussion of how art determines our response to nature. Pairing Niagara Falls, the greatest attraction of the East, with Yosemite, the book shows how 19th-century artists kick-started the enduring urge of Americans to leave the city and marvel at the nation's natural monuments.

After a couple decades or so of Yosemite gigantism, a splinter group of California artists migrated to the coast, where the muted, fog-bound beauty of Monterey "displaced Yosemite in the artistic imagination as California's holiest natural cathedral," writes Scott A. Shields in Artists at Continent's End: The Monterey Peninsula Art Colony, 1875-1907 (University of California Press; 357 pages; $34.95 paper).

Starting with the original Bay Area bohemian, transplanted French artist Jules Tavernier, artists depicted the wave-battered cliffs and wind-beaten Monterey cypresses of the peninsula bathed in a soft light, turning landscapes into tonalist paeans to spirituality. Shields' detailed historical approach illuminates a little-known but significant segment of the state's art history and makes this one art book whose prose matches its paintings.

Prints Charming

Next to Ansel Adams, no 20th-century photographer is more closely associated with our vision of the California wilderness than climber-turned-photographer Galen Rowell, who died in a plane crash in 2002. Galen Rowell: A Retrospective (Sierra Club Books; 288 pages; $50 cloth), a loving, large-format collection, shows off Rowell's ability to do in color what Adams did in black-and-white. One stunning two-page shot, Winter Sunset, Gates of the Valley, encompasses snow-topped river rocks with granite peaks rising out of a misty blue into a glowing orange as they catch the last rays of the day's sun.

The volume contains photographs from the world's remote places, but I find the California shots to be the most arresting. In his 1972 vista of a glowing, blue-cheese-mottled full moon dropping behind a swoop of the Eastern Sierra, the colors are so eerie we might as well be witnessing a moonset over Mars. Appreciative essays by his colleagues and friends add a human touch to these almost superhuman shots of nature.

Roadside California

There is more to the Golden State than majestic redwoods and picture-perfect waterfalls. There is, for instance, the world's largest thermometer in Baker off Interstate 15, which stands a mere 17 feet shy of Lady Liberty herself. There is Bubblegum Alley in San Luis Obispo, a 40-foot stretch of concrete encrusted with masticated chewing gum from the mouths of Cal Poly students. And there is, of course, the Rosicrucian Church, right here in San Jose.

These and a wealth of other outré roadside attractions (some real and some known only to legend) are described and illustrated in Weird California: Your Travel Guide to California's Local Legends and Best Kept Secrets by Greg Bishop, Joe Oesterle and Mike Marinacci (Sterling; 304 pages; $19.95 cloth, a bargain). Did we mention Frenchman's Tower in Palo Alto, a crumbling brick what's-it on Old Page Mill Road, built in the 1870s for purposes too obscure to fathom now?

In a more practical vein, Best of California's Missions, Mansions and Museums by Ken and Dahlynn McKowen (Wilderness Press; 248 pages; $21.95 paper) traverses the state with useful capsule guides to popular and lesser-known attractions. The recommendations range from the off-beat—the Lava Beds National Monument Visitor Center Museum near Tule Lake—to the culturally cutting edge: the de Young Museum in Golden Gate Park. Each write-up serves up the vitals (hours, directions, etc.) in an easy-to-read format. My only complaint is that San Jose gets short shrift—surely we have more than the Winchester Mystery House to entice visitors? What about the new state-of-the-art home of the San Jose Earthquakes? (Ah ... we'll get back to you on that.)

Seers

Anyone who has enjoyed the "Family Legacies" show now at the San Jose Museum of Art will want to explore further Betye Saar's evocative and provocative mixed-media and assemblages in Betye Saar: Extending the Frozen Moment (University of Michigan Museum of Art/University of California Press; 176 pages; $39.95 cloth). Saar, who grew up influenced by both the Watts Towers and the boxes of Joseph Cornell, combines found objects with a sense of history—especially about the African American experience.

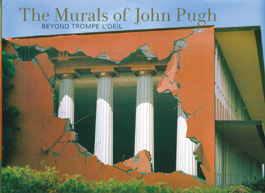

Los Gatos artist John Pugh is as much magician as painter. His exterior wall-size murals (some of which can be found in Los Gatos and San Jose) can fool the viewer with astonishing optical tricks. For a Mexican restaurant in Los Gatos, Pugh painted crumbling walls giving way to reveal an ancient Mexican temple. The illusion of depth is so strong, that passers-by are tempted to step right into the imaginary space as if entering a portal to another world. Kevin Bruce discusses Pugh's technique and vision in The Murals of John Pugh: Beyond Trompe L'Oeil (Ten Speed Press; 155 pages; $35 cloth).

Send a letter to the editor about this story.

|

|

|

|

|

|