Keeping the Faith

Early Santa Clara Valley residents welcomed a devoted community of Jews--even publicly lynched two murderers of a Jewish youth on its behalf. More than a century later, their descendents lost all traces of their Jewish heritage. Is it possible that life here--with assimilation and intermarriage--has been too good?

By Dan Pulcrano

The '49 Gold Rush quadrupled San Jose's population, and the city of 4,000 rode high through its short-lived glory as California's capital. As legislators toasted the state's impending admission to the union with a thousand drinks, Leopold Hart, a Frenchman from Alsace-Lorraine, boarded a transatlantic steamship to join his half-brother, Lazard Lion, on the new frontier.

The two businessmen were among the early members of the city's tiny Jewish community, which by 1860 numbered 50 and had secured a 10-acre cemetery plot. The following year, 10 men organized a Hebrew society to bury the dead, comfort the ailing and pass Jewish traditions on to the young. They declared 50-cent-a-month dues and named it Bickur Cholim, after the Jewish mitzvah of visiting the sick.

By all accounts, the Israelites, as they were called, were well accepted and quickly became anchors of the city's early civic and commercial life. Lion headed San Jose's Bank of Italy, which grew into the Bank of America; Hart founded what became the largest department store between San Francisco and Los Angeles. For close to a century, Hart's was the retail giant of downtown San Jose, which at the time was the region's unrivaled commerce hub.

The Rabbis

While their names may carry less cachet than the Levis and the Strausses, the Steinharts, the Haases and the Sterns in the city to the north, whose legacies are enshrined in the Issac Stern Grove in Golden Gate Park, the SF Museum of Modern Art, the SF Public Library and the Steinhart Aquarium, the South Bay community, equally public-spirited but less highbrow, contributed such enduring enterprises as Kragen Auto Parts, Midas Mufflers, A. Hirsch & Son Jewelers and the Markovits and Fox metal recycling concern. Today, such Silicon Valley superstars as Intel, Hewlett-Packard, 3Com, Oracle and Applied Materials are run, respectively, by Andrew Grove, Lewis Platt, Eric Benhamou, Larry Ellison and Dan Maydan, members of the same small, ancient tribe.

Some helped revitalize downtown San Jose after its decline, building the Fairmont Hotel and Park Center Plaza as well as cultural institutions such as the San Jose Symphony (conductors George Cleve and Leonid Grin). Others have been active in law and government. San Jose Mayor Susan Hammer, while not born Jewish, attends religious services from time to time with husband Phil, a past president of Temple Emanuel, formerly Bickur Cholim.

When the community erected its first synagogue in 1870, gentiles ponied up as well, an irony not lost on the French, who wrote in Paris' Archives Israelites: "Showing the peculiarity of Christians and Jews in America, a society composed essentially of non-Israelites wanted to contribute 2,000 francs ($400) for the construction of a new temple."

The community dedicated a temple that August at S. Third and San Antonio streets. Families as far away as San Francisco and San Juan Bautista traveled by wagon to attend services in the $5,000 building that the local press had promised would be "highly ornamented and really beautiful."

With doors open, Bickur Cholim hired its first rabbi for $100 a month. Little is known about Rabbi Henry Lowenthal, except that he didn't work out and was discharged a year later for "misconduct in office and violation of contracts." After an interim replacement, the congregation hired its first ordained rabbi in 1873. The board was more cautious this time. They hired Myer Sol Levy on a month-to-month basis after motions for year-long and half-year contracts failed to clear the board.

In May 1874, 10 teenage girls dressed in white with flower sprigs in their hair marched into Bickur Cholim's pulpit to be confirmed. Six months later, 13-year-old Jesse Levy became the congregation's first Bar Mitzvah.

Though they represented less than 1 percent of the city's population, the pioneers left a legacy still visible today. Their family names can be spotted on the Lion Building's façade at Second and San Fernando, on the brick wall of the old Hart's warehouse along the railroad tracks behind the Arena and on the storefronts of Stern's Luggage at Valley Fair and Oakridge shopping centers. Clay Stern, great-great-grandson of Bickur Cholim vice president Marcus Stern, will be the fifth-generation operator of the county's oldest family-owned business.

Marcus Stern ran a saddle and harness business that diversified into horse blankets, steamer trunks and fire hoses. His son, Fred Stern, served on both the San Jose City Council and the county Board of Supervisors and attended temple along with his wife, Hattie. Son Harold intermarried, and subsequent generations were raised as Protestants, according to family members.

The Stern story mirrors those of the other descendants of the original Jewish families, who are more likely to take communion or decorate a Christmas tree than pin a mezuzah to their door frame. Absent the persecution that Jews faced in Europe and some parts of the U.S., the valley's Jews never constituted a distinct community. There was never a valley equivalent of L.A.'s Fairfax Avenue or New York's Lower East Side. Indeed the tolerant residents of the fertile valley, with its sunny climate, easy prosperity and tradition of assimilating immigrants of diverse origins, mixed so well with the people of the book that were it not for successive waves of newcomers, the community would have simply melted like French butter into the valley's ethnic stew.

Paul Lion, Lazard's great-grandson, says his forebear married an Episcopalian and his grandfather was raised that way. "The family home was at Second and St. John, right across from the Episcopal Church," Lion says. "My great-grandfather had the minister over for dinner every Thursday night. It was supposedly a bribe so the church wouldn't ring the bells before 10 on Sunday."

Leopold Hart's family kept the faith a generation longer. The patriarch journeyed to France in 1863 and wed 17-year-old Hortense Cahen the next year. They had six daughters and one son, Alexander, who was active in the temple and took over the family business when Leopold died in 1904.

Perhaps no family better exemplified the assimilation of San Jose's Jews into the dominant culture than the Harts. Leopold supplied the single tuxedo that the members of the San Jose Orchestral Society, known later as the San Jose Symphony, passed among themselves for individual portraits, which were then meticulously spliced into a group portrait.

Alexander married a Catholic girl from Baltimore in 1910, and the kids were raised in a secular home at which both the local rabbi and local priests dropped by. Some Hart children accompanied Alex Sr. to temple as well as attending the Jesuit-run Bellarmine school. Son Alex Jr. says, "There was never any discussion [of religion] in the home. My father enjoyed the holy days and would attend temple. My mother enjoyed Easter and Christmas."

Alex Sr. built Hart's into a prosperous enterprise. He lived in what was "considered by many to be the loveliest residence in San Jose," author Harry Farrell writes in Swift Justice, and, "in San Jose's mercantile hierarchy he moved on a special plane of respect as an honest dealer, community leader and philanthropist."

Hart was a member of San Jose's exclusive men's club, the Sainte Claire Club, and a president of the Chamber of Commerce. Tragedy struck the Hart family when Alex Sr.'s 22-year-old son, Brooke, who was being groomed to manage the department store, was kidnapped for ransom in 1933. It was the same year that San Jose's small B'nai Brith chapter resolved "that a committee be appointed to get signatures to a petition to the President of the United States against the mistreatment of Jewish people by the Hitler regime in Germany," which had come to power earlier in the year and instituted a boycott of Jewish shops, banks and department stores.

Christopher Gardner

San Jose was a far cry from Germany, or even Atlanta, Ga., where pencil factory owner Leo Frank in 1913 was falsely convicted of murdering a 13-year-old girl after a prosecutor inflamed local passions with innuendo about Jewish men seeking gentile girls for their pleasure. The crowds outside the courtroom screamed "Hang the Jew" as the jury selection transpired inside. Following the presentation of the state's flimsy case, the jury took but four hours to convict Frank, though the state's governor subsequently recognized the sham and commuted Frank's sentence. Nonetheless, in 1915, a crowd of well-known local citizens stormed the prison farm where Frank was held and hanged him from an oak tree in Marietta, Ga. A postcard of the lynching was sold throughout the South.

Antisemitism in America rose to its highest historical levels during the 1930s, fueled by the Great Depression, Hitler's ascension to power and the rise of fascism elsewhere in Europe. Employment and housing discrimination and anti-Jewish education quotas surfaced in many parts of the country, and American demagogues targeted Jews in their political rhetoric.

San Jose, however, couldn't have been more different. In picking Brooke Hart, Farrell writes, his kidnappers "could have chosen no victim whose popularity and place in the community would more surely guarantee the violent retribution that followed."

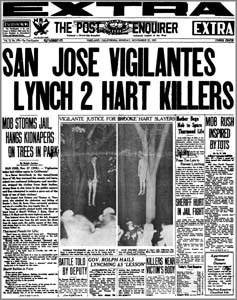

When the brother of a local church organist and his sidekick were arrested and confessed to tossing the beaten and bound young man off the San Mateo bridge, San Jose's citizenry was enraged. After Brooke Hart's crab-eaten corpse was found by fishermen in the bay's shallow waters more than a week later, an ugly mob gathered outside the steps of San Jose's jail. With a wink from California Gov. "Sonny Jim" Rolph, nearly 40 men rammed the doors and stormed the jail, threw ropes around the killers' necks and dragged them across the street to St. James Park, where they were beaten and lynched as thousands watched.

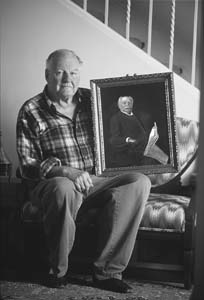

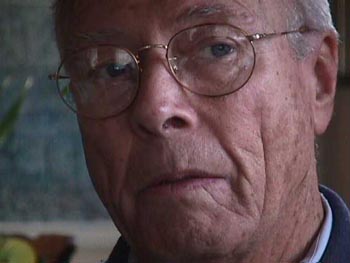

Thirteen-year-old Alex Hart Jr. had seen the naked bodies of his brother's confessed murderers dangling from the trees in the park. Fifty-five years later, the soft-spoken retired merchant, now 77, sat in the living room of his Los Gatos apartment and volunteered some thoughts about "that horrendous time in our family's life," which the Harts left undiscussed for nearly half a century, until journalist Farrell coaxed two Hart siblings into breaking their silence.

With his father's foot-long meerschaum pipe framed in a glass case behind him, Hart is dressed in all blue, including a blue pinkie ring. The Harts, he confirms, were perceived generally as a Jewish family, even though the children attended Catholic schools and Father Collins often dropped by the house to play poker.

Hart believes that the mob violence was "absolutely" a statement of support for his family. "It was an expression of how the community felt about my family and about my brother. He was loved."

Of the vigilantism, he is careful to say, "It wasn't the right thing to do." And after a pause, he adds, "But they got what they deserved, if you want to know my personal opinion."

It's a tragic irony that in the year Hitler opened his first concentration camp for Jewish prisoners, San Jose demonstrated its brotherhood with a violent expression of grief and sympathy for the city's best-known Jewish family, In other places, Jews were being killed. San Jose gained notoriety by executing the Jew-killers.

In another park, three blocks to the south, another defining moment came for San Jose's Jews when in 1994 board members of the Christmas in the Park organization elected to transfer a religious nativity scene off of public land to the front lawn of St. Joseph Cathedral across the street. The move came in response to suggestions from several individuals, this writer included, who believed that church-state separation was constitutionally correct.

Inflamed by a front-page Mercury News article that suggested that exhibit organizers had "exiled the baby Jesus" from Plaza de Cesar Chavez because of Jewish community pressure, callers jammed phone lines at City Hall and Christmas in the Park offices. Several influential members of the Jewish community sought to distance local Jews from the crèche separation.

"I deeply regret that the issue was raised," said Lil Silberstein, executive director of the local office of the National Conference of Christians and Jews. She expressed relief when the crèche was moved back to the public park a few days later. "I just didn't want the controversy to continue," she added.

Retired department store executive Alex Hart Jr. says the lynching of his brother's killers "was an expression of how the community felt about my family and about my brother."

Ugly postings began to show up on the Mercury's posting area on America Online. A "GMGraves" wrote: "To ... all of the Jews who feel hurt by having to view this scene, I have this to say: My heart really bleeds for you. You comprise less that 5 percent of the population of a predominantly historically Christian nation. If you do not like the icons of the predominant religion in this country, then I say to you that there are two simple alternatives: either don't look, or leave. I know a country where your religion dominates and where Christian icons are rarely, if ever, seen. A country where religious and ethnic freedom is suppressed to the point of violence. But that shouldn't worry you. You are Jews, God's chosen people; your point of view prevails there. The place is called Israel. Go there. If you Jews are offended by my religeous icons, I'm even more offended by yours. If I never see another Star of David, or another minorah (sic) again, it would be too soon."

"Jrduke" added, "Our nation was founded with Christianity in mind. By definition, one of the common threads which holds any nation together, is a common religion. ... It should be clear to all that America was founded upon Christian heritage and that it is alright for our government, albeit in non-demonstrative ways, to place a Christian symbol in a public place. GOD BLESS AMERICA."

And at the Plaza, a man who identified himself as a Willow Glen appliance repairman carried a placard urging the sacrifice of liberal Jews. "Cut their hearts out," he amplified.

Suddenly San Jose was no longer the tolerant bastion of religious harmony it once appeared to be, as the virtual lynch mob shouted down any opportunity for intelligent discussion. The unwritten compact for prosperity and community acceptance of a religious minority had been its tacit agreement to not make waves. When they had fit in, assimilated, intermarried and went along with the conventional wisdom of the majority culture, things went swimmingly. As members of the greater community Jews were well accepted into the social circles and institutions of the valley's elite. But any attempt to assert rights on a controversial subject could bring about a biblical wrath.

In general, San Jose has been relatively free of antisemitism, although some longtime residents can cite an example of discrimination or an antisemitic remark. Yeshiva kids in the late 1970s were sprayed with fire extinguishers by a motorist, and all the tombstones in the Home of Peace Jewish cemetery were once knocked over.

Of Silicon Valley's 1.7 million residents, only 35,000 or so--about 2 percent--identify themselves as Jews, according to the Jewish Federation of Greater San Jose. Fifteen percent--about 5,000--are affiliated with a temple or other Jewish organization. By comparison, Jews in San Francisco represent almost 12 percent of the population. San Francisco has 28 congregations within the city limits; the entire South Bay, with more than double the population, has 21.

At the local level, political activism by the Jewish community avoids controversy and is frequently limited to taking defensive positions, such as protesting newspaper editorials critical of Israel. There is no large Chanukah menorah in a central park, as there is in San Francisco's Union Square. Jewish organizations here have less funding and fewer members than in many comparable cities, and few historical materials about the valley's Jewish community exist in the public arena. This article is one of the first pieces in the general press to examine the Jewish community's local impact and role.

Nonetheless, it's clear that Jews have been prominent in shaping the valley in which we live, from its early settler days, through its periods of hypergrowth, to the bustling Silicon Valley we know today. Temple Emanu-El historian Jane Schwartz attributes the absence of ethnic conflict to the fact that everyone came to the valley together with nothing, determined to make something of themselves. "They had no baggage," she says.

To some eyes, the local organized Jewish community could appear ingratiating, assimilationist and meek. To others, it has been a small price to pay for the harmony and prosperity that the area's Jewish citizens have for 150 years enjoyed.

Cecily Barnes contributed portions of this article.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

From a turn of the century postcard.![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

The Retail Tradition

Pioneer Meyer Bloom

Havdalah & History celebration

Home of Peace Jewish cemetery![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

Rabbi Freund celebrated Jewish traditions with San Jose's future first husband, Phil Hammer, on the right.

Leopold Hart founded a retail dynasty. Hortense Cahen married Leopold Hart.

Hortense Cahen married Leopold Hart. Paul Lion holds a portrait of his great-great-grandfather, Lazard.

Paul Lion holds a portrait of his great-great-grandfather, Lazard. The Oakland Post Enquirer published photos of the hung kidnappers, which other Bay Area dailies thought better of.

The Oakland Post Enquirer published photos of the hung kidnappers, which other Bay Area dailies thought better of.

Dan Pulcrano

Hart supplied a single suit to the San Jose Orchestral Society, which members passed around to create a composite photo.

Metro wishes to express its appreciation to the following individuals and organizations who shared information and photographs: Temple Emanu-El, Temple Beth David, Stephen Kinsey, Clyde Arbuckle's History of San Jose, Alex Hart Jr., Memorabilia of San Jose, Leonard McKay and Harry Farrell.

From the March 12-18, 1998 issue of Metro.

![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)