![[Metroactive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)

[ Music Index | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

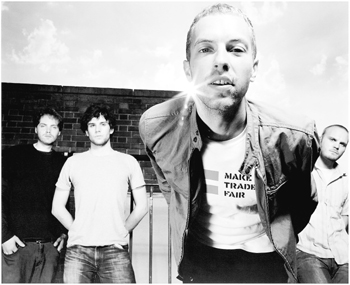

Coldplay. How Much Will You Pay? Who should get the best Coldplay seats--the die-hard fan that camps out overnight or the casual fan with a huge disposable income? If Ticketmaster's bid-for-tickets scheme is implemented, the answer could be none of the above. By Jim Harrington IT'S LIKE a scene out of a movie: A kid camps out overnight to get tickets to see his favorite band in concert. All that effort and time pays off, and the young fan gets front-row tickets. Awesome! Now, the fan will get to see what Dave Matthews looks like up close. Those days are long gone--if, indeed, they ever existed--as concert ticket prices have soared into the stratosphere. Factor in the best seats for the biggest shows always seeming to end up in the hands of scalpers and ticket brokers, who turn around and sell them for many times face value, and you have about as much chance of scoring front row to Simon and Garfunkel at the HP Pavilion as the Sharks have of hanging a Stanley Cup banner up in the same building this season. And the situation could get even tougher. Ticketmaster, the world's biggest ticket seller, is in the process of perfecting a system that will allow artists and promoters to auction off choice tickets to the highest bidders. Although the ticketing giant is still experimenting with the software, this new system--where fans compete against each other to get the seats they want--could potentially revolutionize how tickets are sold on the primary market. You really want those tickets to Primus? They're yours to have--as long as someone doesn't outbid you. Understandably, some concertgoers are worried about what this new system will mean to their wallets. They are also concerned that this process could shut out many true fans, whose credit card limits might not be as high as their enthusiasm levels. "The big problem is a 16-year-old kid who lives and breathes Coldplay will never in a hundred years be able to outbid me, a more casual Coldplay fan," says Miguel Rodriguez, a 30-year-old Mountain View resident who works as an assistant website manager for UCSC Extension. "And both of us combined wouldn't be able to outbid a CEO who 'really likes that one song from Coldplay.'" Some would argue that that situation isn't much different from the one that has existed for years thanks to a thriving secondary market for tickets sold through brokers and online auction houses like eBay. "If you want great seats, and you have the money, you can get them. That's not a new concept," says Gary Bongiovanni, editor of the concert-industry trade magazine Pollstar. "You go and talk to people in the front few rows, and you'll find that they probably got them from a ticket broker and paid a lot more than face value."

Winter Music Guide 2003 The Fingerbangerz The Faction David Bowie The Matches Jucifer The Ataris Hieroglyphics Primus Evanescence The Brian Setzer Orchestra Good Charlotte Hot Water Music Mya The Polyphonic Spree Ticketmaster's new bid-for-tickets system Winter music listings Ticketmaster is very aware of the situation that exists in the secondary market. In a way, the company's foray into the world of ticket auctioning is an attempt to cut out the middleman, let the public set the market value for the tickets and put the earnings in the so-called proper pockets. As it exists now, the artists and venues don't benefit from tickets sold through brokers for many times face value. With the new online bidding process, the artists, venues and promoters would be the ones who reap the rewards. "I think more and more, our clients--the promoters, the clients in the buildings and the bands themselves--are saying to themselves, 'Maybe that money should be coming to me instead of Bob the Broker,'" Ticketmaster president/CEO John Pleasants was quoted as saying in The New York Times. So far, Ticketmaster has successfully tested the system twice. Last year, consumers bid on ticket packages to see Lennox Lewis/Kirk Johnson fight at the Staples Center in Los Angeles. The process was also used for a recent UNICEF benefit performed by Sting at the Hammerstein Ballroom in New York City. Things didn't turn out so bad for fans in the case of the Sting show. Ticketmaster auctioned off 1,680 floor seats using a uniform price format, where prices were set based on the lowest accepted bid. That amount turned out to be $90 per ticket--a reasonable sum given the performer, the venue and the market. As of yet, this process has yet to be tested by Bay Area promoters. Representatives at both Clear Channel/BGP and Another Planet declined to be interviewed for this article, instead waiting to see how this new ticketing mechanism is implemented in other markets. Although much of the attention devoted to this issue has centered around the best seats for the top shows, Ticketmaster spokesman Larry Solters quickly points out that this system might even have a greater effect on the nose-bleed seats at less-popular shows. In these tough economic times, roughly 50 percent of tickets go unsold each year. Half-empty houses mean fewer concession and souvenir sales, less parking revenue and a much less exciting concert environment for both fans and performers. Putting amphitheater lawn seats and other hard-to-sell tickets up for bid--thus letting the public set the market value--could translate to fuller houses at venues across the country. And likewise, that could actually result in lower-than-face-value ticketing in some situations. "If we can sell the seats and fill the house," Solters says, "that's the mandate of the venue, the promoter and the artist." And thanks to those famed per-ticket service charges, that's Ticketmaster's mandate as well.

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the October 30-November 5, 2003 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.