![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Frankly Speaking: Hot dog vendor Judy Chung now operates her cart in front of the Civic Center, in the place once occupied by former employee and well-known 'hot dog man' Leo Healey. Chung believes Healey was forced out by authorities.

Vendor Bender

Leo Healey, a local celebrity who sold frankfurters to prosecutors and cops in front of the courthouse, wanted to get on with his life. But his 17-year-old past as a convicted child molester ultimately got in his way.

By Will Harper

ON HIS LAST day at his familiar W. Hedding Street hot dog stand between the Main Jail and the Hall of Justice, Leo Healey did something his regular customers would say he did all the time: offer his help.

According to police, a customer asked Healey to look after his 4-year-old stepson while he made a scheduled Oct. 19 court appearance.

For at least an hour, the boy sat and watched Healey peddle frankfurters and joke with customers while waiting for his father to return. It was a brisk autumn day and Healey put his teal San Jose Sharks jacket around the boy to keep him warm, witnesses recall.

It might seem odd for someone to leave his child in the care of a hot dog vendor, but then nearly everyone who had business in the Civic Center area knew Leo. If they didn't know him by name, they knew his generic nickname, "the hot dog man."

After a decade of selling hot dogs, snacks and sodas five days a week from the same sidewalk spot, Healey had become something of a San Jose institution.

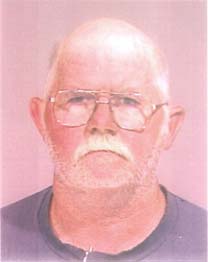

He was easy to recognize because he always seemed to wear the same outfit: a baseball cap, jeans and a Sharks jacket that barely fit over his big belly. He looked older than his 54 years--he was completely gray, including his trademark stubble beard.

Over time, he developed a reputation for being more than a simple hot dog vendor--he was a street-corner guru. Lawyers tested legal arguments out on him. Alcoholics and addicts asked for his insights as someone who claimed more than 15 years of sobriety.

If Healey wasn't giving his opinion or his advice, he was trying to make himself useful in other ways, acquaintances say. If a nearby meter expired, he'd plug it with a few coins so the car-owner wouldn't get a parking ticket. If a regular customer was short on cash, Leo would extend them credit. He often gave kids free food, according to a local defense attorney.

San Jose Mercury News columnist Leigh Weimers even dedicated a complimentary Sunday feature story to Healey last year: "Hot Dog Vendor Makes Civic Center a More Civil Place."

But on that day of impromptu babysitting last month, Healey's desire to be helpful would catch the attention of local law enforcement.

The police knew something about Healey that his boss and loyal customers didn't know: He was a registered sex offender who had been convicted in 1983 of sodomizing and forcing oral copulation on a 5-year-old boy who lived in his Palo Alto home.

That afternoon, two plainclothes police officers came by Healey's hot dog stand and took away the boy to protective custody. Then Tom Jensen of the police department's permits unit--which issues and regulates vendors' licenses--summoned Healey for a talk.

Jensen also paid a call to Deputy District Attorney Terry Bowman, who was prosecuting a 34-year-old Milpitas man named Victor Castillo on charges of domestic violence and child abuse. As it turned out, the boy left in Healey's care was Castillo's stepson. Because of the child-abuse charge against him, Bowman says, Castillo wasn't even supposed to have any contact with the child. After getting Jensen's call, Bowman filed another charge against Castillo for violating a court protective order.

When Healey arrived at the police department's permit unit around the corner from his stand, authorities asked about why he was looking after Castillo's stepson.

They also asked him about another incident brought to their attention by a child-abuse prosecutor a month prior. According to law enforcement sources, the prosecutor had been walking by Healey's stand and saw him wiggling a hot dog in an adolescent boy's face in an allegedly lewd manner, asking, "Is this what you want?"

Healey told police he was only trying to help out Castillo, and he didn't even remember the other incident, San Jose police spokesman Rubens Dalaison says.

Even though police had no evidence that he had done anything illegal, Healey surrendered his vendor's permit to authorities before he left. Dalaison says, "He surrendered his permit on his own volition."

HEALEY'S BOSS, JUDY CHUNG, who runs a fleet of hot dog carts called Super Treat, says that police pressured him to give up his permit and the hot dog stand. It wasn't the first time Healey's snack-stand operation had come under police scrutiny.

San Jose attorney Dan Mayfield represented Healey about four years ago when police, after learning that Healey was a registered sex offender, threatened to revoke his vendor's license.

Mayfield says that at an internal police department hearing more than two dozen people--including employees of the district attorney's office--vouched for Healey's character. Afterward, the permits unit decided to let Healey keep selling hot dogs.

Chung, who had to shut down her other two stands to take over for Healey after he quit in October, says she did not know about Healey's criminal background. "He seemed like a nice chap," Chung says after handing a sheriff's deputy his change, "but you never know."

Chung adds, "He likes to joke around."

Mountain View attorney Milford Reynolds, a regular customer of Healey's, suggests that the vendor's penchant for wisecracks may have gotten him into trouble. One of Healey's recurring jokes, says Reynolds, involved teasing newcomers who made the mistake of asking for just a hot dog. Healey would oblige by retrieving a hot dog with his tongs and then attempt to hand the bunless frankfurter to the puzzled customer, with the punchline: "Well, you didn't ask for it on a bun."

Reynolds says that it's possible that the prosecutor who walked by the stand the day of the alleged hot dog wiggling incident with the adolescent boy mistook Healey's gag for a lewd interaction. "I can see how somebody not seeing the conversation fully might get the wrong impression," Reynolds acknowledges.

ACCORDING TO COURT records, Healey grew up in Malden, Mass. He and his older sister were raised by their father and paternal grandmother. His father sexually abused him when he was around 10. When Leo tried to tell his grandmother about it, court documents read, she didn't believe him.

He graduated from high school in 1964 and a year later left Massachusetts to join the Army for the next three years, including a 12-month stint in Vietnam as a cook.

His trouble with the law started after he moved to California in 1980 with his second wife, during what he described to court-appointed psychiatrist Douglas M. Harper as "my drinking days." At the time, court records say, Healey molested a 5-year-old boy in his home for approximately six months to a year. After discovering the sexual abuse, his now ex-wife reported Healey to the police, who arrested him in July 1982.

The following year Healey was convicted and sentenced to six years in Vacaville state prison for engaging in sodomy, oral copulation and lewd conduct--all felonies--with a minor under age 14. After serving two years and three months of his sentence, he was paroled.

Shortly after being released from prison, Healey met his third wife, a postal worker, on a blind date. Healey told Dr. Harper that his wife knew all about his past.

IN 1989 HEALEY started working at the Civic Center hot dog stand that made him a sidewalk celebrity. A sexual assault prosecutor says that a few people in the district attorney's office weren't thrilled by Healey's presence there. But if a "290"--the penal code number for a registered sex offender--was going to work somewhere, it might as well have been at a place where authorities could keep an eye on him.

As far as authorities can ascertain, Healey has been a law-abiding citizen in this county since his incarceration without committing any other sexual assaults since he left Vacaville.

He's even raised money for the San Jose Rhinos' "Corp for Kids" program, which takes private donations to buy tickets for poor kids to see professional roller hockey games at the Arena. "My ticket person was quite impressed," says Rhinos vice president of operations Jon Gustafson, "by the way Leo would go out and push the program."

Gustafson says that Healey did not have any contact with children through the ticket-giveway program.

Healey and his wife, both big Sharks fans, are also active members of the Hammerhead Booster Club. According to the fan club's website, the Hammerheads also have a Sponsor-a-Child ticket program for poor kids. Club board member Bob Corwin declined to comment as to whether Healey has any direct contact with children through the program and referred questions to club president Rene Watkins. Watkins did not respond to phone calls or emails.

BY ALL INDICATIONS, Healey had made serious attempts to move on with his life. In 1994 Healey filed for a certificate of rehabilitation and pardon in Santa Clara County Superior Court. Healey told court officials that he wanted the certificate so he could get on with his life and find a better job than selling hot dogs for $800 a month.

Criminal defense attorneys submitted letters of recommendation on Healey's behalf: Public defender Zach Ledet lauded Healey's work with alcoholics in hospitals and institutions. Lawyer Howard Kane gushed, "Leo is truly adored by all." Attorney Dan Mayfield described him as "the most honest person I know."

But court-appointed psychiatrist Douglas Harper seemed skeptical of Healey's motives for obtaining the rehabilitation certificate. Upon questioning, Healey acknowledged that the certificate would allow him to make contact with the boy he molested in 1982. Healey explained that in Alcoholics Anonymous, the ninth step suggests that members make amends with the people they have hurt.

Harper observed in his written evaluation to the court, "[Healey] has somewhat of a pensive look. ... Impulse control is adequate. Insight is limited. When his rationale for wanting to seek contact with [the boy] is discussed, it seems to focus primarily on the needs he [Healey] has to bring about some resolution."

Ultimately, Harper didn't recommend Healey for a rehabilitation certificate, saying he needed more information. On July 23, 1997, Judge Lawrence Terry denied Healey's request without prejudice, meaning he could apply again in the future.

EVEN THOUGH HEALEY can reapply for legal absolution later, it won't be in a favorable political environment. After all, just three years ago, Gov. Pete Wilson and the state Legislature approved chemical castration for twice-convicted child molesters.

Dr. Stewart B. Nixon, a Palo Alto psychologist who specializes in treating sex offenders, says that the California justice system has all but given up on rehabilitating child molesters despite the fact that there's not enough room to keep all convicted pedophiles behind bars.

Some like Leo Healey return to the world and try to lead productive lives. That's not easy, says Nixon. Sex offenders often find it difficult to overcome the stigma that goes along with their past crimes.

"Yes, these people can do very well," Nixon says, "but if they can't find work, have no money for therapy, the question is, What are they supposed to do? Society says, 'You should have thought of that before you did what you did.' "

Many patients, Nixon says, "often end up doing menial work because no one wants to take a chance on them."

Within the past couple of weeks, attorney Milford Reynolds--a regular customer of Healey's--spotted Leo while driving down North First Street near the House of Pancakes on the corner of Jackson.

Reynolds honked his horn and pulled over. The two chatted for a few minutes and caught up with each other.

Standing only a few blocks away from the hot dog stand he ran for 10 years, Healey told his old customer that he was talking to a friend about getting him another job. He was getting on with his life, though perhaps not in the way he envisioned when he applied for a certificate of rehabilitation and pardon five years earlier.

Reynolds describes Healey's demeanor as "fair to middlin'. He definitely wasn't his usual jolly self."

His days as "the hot dog man" were over.

Healey didn't respond to phone messages and a letter from Metro asking for an interview.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © 1999 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

![]()

Photograph by George Sakkestad

Leo Healey

From the December 2-8, 1999 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.