![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

C And Be Seen: The silent stalker of the '60s generation

There could be worse things than having a chronic, life-threatening, stigmatizing virus. No, really.

By Kelly Luker

LET'S JUST get this out of the way right now. Maybe Bill Clinton didn't inhale back in the '60s, but I did. And snorted and drank to excess. And injected. A lot. That fun little decade gave me enough material to pen overwrought confessionals for a lifetime, entertain my friends in rehab and remind me that I can visit hell on earth anytime I want.

This is not the beginning of a tell-all memoir, but merely a bit of history that is relevant to a here-and-now situation that found its roots in that decade.

It appears that along with vintage Fillmore posters and bad memories, I and about 4 million other people in America have another token from that groovy era: hepatitis C.

"The Silent Killer," journalists and health professionals call this virus that can slowly destroy the liver. "The Shadow Epidemic," it's been labeled, because of the 4 million folks in the United States who have hepatitis C, according to the Centers for Disease Control, 3 million don't know it. Maybe our collective ignorance can be chalked up to a disease that has garnered minuscule media coverage, at least compared to AIDS, cancer or even Legionnaires' disease. The lack of attention could also be because what is known about the hepatitis C virus (HCV) is dwarfed by the unknown: amid a maze of contradictory theories and studies, there's the plain old terrifying fact that not everything is known about its transmission. Scientists theorize that it can be sexually transmitted, but they think this happens fairly infrequently. Sometimes the virus moves fast, but usually it is glacially slow. Maybe it will kill, maybe its host will die of old age first.

I'm willing to bet my love beads that most of the public ignorance about this disease is spawned by fear and denial. And that duo feeds on what researchers know for sure: hepatitis C is a blood-borne disease, most often spread (in this country, at least) by intravenous drug use. I have what medical sociologists term a "sin" disease. Like AIDS in this century or leprosy in previous ones, just the phrase "hepatitis C" can telegraph a catalog of stigmas about its host. Junkie. Sinner.

Before the non-junkies and righteous start feeling too relieved about their distance from this disease, there are a couple of things worth knowing. First off, it is not only needle users who contract hepatitis C. My priest friend Father Bill Rainford never darkened the doors of drug rehab, but he did have a heart transplant 14 years ago that also gave him hepatitis C through the blood transfusion. Before scientists had perfected the test that would screen blood donors for HCV in 1992, the chances of contracting hepatitis C through blood transfusions were as high as one in 10. However, Uncle Sam did not exactly rush out to let those folks know who they might be.

Although the government knew by 1990 that more than 300,000 people received HCV-tainted blood, the Food and Drug Administration was still debating until last year whether to tell those 300,000 that they had a potentially deadly disease. In 1998, blood banks began the laborious process of tracing back through their records. Then there are others diagnosed with hepatitis C who have a kind of Immaculate Infection: they swear they never picked up a needle, never had a blood transfusion, never worked in the health field (where they might have been subjected to accidental needle sticks) and never had promiscuous sex. Those folks fit in another Bermuda Triangle of this disease that epidemiologists have identified--the approximately 10-40 percent with no known vectors of transmission.

This has left a lot of people with understandable anxiety, and has left the CDC theorizing that the virus could have traveled through a rolled-up dollar bill used when snorting cocaine, from homemade tattoos and piercings, even through the use of shared razors or toothbrushes.

Hepatitis C earned its label as the Silent Killer precisely because the virus leaves so few noticeable tracks of its presence. The most common symptoms--if any--are fatigue, malaise and depression: three signposts of just about every stressed-out fin de siècle yupster in this country.

Wake-Up Call

YEARS BEFORE I was diagnosed, I had learned to factor in a nap almost every day. It was no mere indulgence; without one I would fall asleep at my desk. Sometimes I'd drive home and take a nap; often I'd just head out to the parking lot and curl up on the front seat of my car. Sometimes it was worse; there were months where I could count on three good hours a day. While that may have been a tap on the shoulder for some folks, it didn't occur to me that something physical was wrong. That's because I was struggling with Symptom No. 3--depression. In the early days of substance abuse recovery (the first 10 years or so, in my case), the synapses just don't take too well to all that reality.

Those symptoms--depression and fatigue--also got lost in the flurry of building a new life. I was working hard at a job I truly loved. I had quit smoking and begun training for half-marathons and triathlons. Off hours were still spent with drunks and junkies, but now we went to recovery meetings, socialized and helped each other limp through the days.

It was through a yearly exam with a new doctor in 1992 that I discovered I had hepatitis C. After reading my medical history, she suggested a newly perfected test for a chronic liver disease that seemed to be prevalent among former IV drug users.

The timing of this new diagnosis could have been better. After 12 years of living in Southern California, I was moving back home in the next two weeks to care for my elderly parents. I was ending a relationship and leaving my job, my friends and the gang that stood by me when things were hardest.

But what was most difficult was trying to figure out what this new diagnosis meant. The problem was, the scientific community didn't know very well either. The doctor sat me down and told me what they did know. The hepatitis C virus attacks the liver, potentially destroying it through a scarring process called fibrosis which can lead to serious scarring known as cirrhosis. The liver is a tough little workhorse, she said, able to function with 90 percent of it destroyed. That partially explains the lack of symptoms until it's too late. For most, the virus will take decades before making itself known unless discovered by a sharp doc.

But who will live until old age and who will end up on the liver transplant list--or die waiting--is still a mystery today. Hepatitis Foundation International estimates that 20 percent of us will develop cirrhosis and a quarter of those (5 percent in all) will die.

At this point, there is no solid evidence on who will advance to that final 20 percent or 5 percent. Continued alcohol use can play a major role, but the disease can progress just fine without it.

HCV vs. HIV

IT IS THIS MURKY KNOWLEDGE that may also lead to hepatitis C's media coverage, which is schizophrenic at best. On the one hand, there's the formidable New Yorker warning of "The Shadow Epidemic" (May 11, 1998). But given that the Centers for Disease Control estimate that at least four times as many people are infected with hepatitis C as with HIV, the media attention pales in comparison. A random search of New York Times archives for articles written last year that mention the word "AIDS" kicks back 1,202 hits. By contrast, hepatitis C is mentioned 72 times.

It's not only the media that appear to be stifling a yawn over the Next Big Epidemic. A search of the online medical information database Medline for the word AIDS gets you around 95,500 hits. The yearly international AIDS conference still draws about 10,000 researchers and hundreds of journalists. The National Institutes of Health plan to spend $1.8 billion next year for AIDS research, more than $1,600 per infected person. Contrast these facts with those on hepatitis C, whose sixth international symposium, sponsored by the NIH in June of this year, drew 775 researchers and only one journalist. The NIH will spend about $25 million next year for HCV research--roughly six bucks for every infected person. Looking for research information? Medline returns 9,000 hits for hepatitis C, roughly 10 percent of the number for AIDS.

Maybe the researchers and media are on to something. In recovery groups, HCV is as commonplace as the sniffles in preschool. That is not mere speculation; studies quoted by former Surgeon General Everett C. Koop have found that somewhere between 60 and 100 percent of IV drug users and one-third of alcoholics are infected with the virus. I have long since lost count of how many I know--either personally or anecdotally--with hepatitis C. But perhaps because it is so common and so perplexing, hepatitis C just doesn't find itself the topic of conversation that often. With its two- and three-decades-long incubation, hepatitis C spares its hosts the immediacy or finality of cancer, or AIDS without aggressive treatment. That approximately 95 percent of us with this virus will die of old age, a car accident or a random workplace shooting before our liver rots also gives pause to the crepe-hanging and hand-wringing. It may also be why we have yet to see the liver's equivalent of ActUp, or celebrities sporting little brown ribbons. It's not easy finding the motivation to get political when the rallying cry for our disease is "Just let me grab a quick nap first."

While there is no vaccination for the virus, there is treatment available. Unfortunately, the year-long treatment has a relatively low success rate and a high discomfort factor. A self-injected drug called interferon also used in AIDS treatment or cancer chemotherapy can induce mild flulike symptoms or worse: sweats, nausea, leg cramps, suicidal depression, diarrhea, joint aches, headaches, fatigue and hair loss. While interferon treatment claimed a success rate around 10 percent at best, its recent combination with another drug, ribavirin, has boosted the success rate to as high as 40 percent. Unfortunately, it has also made the side effects even worse. Therefore, doctors do not automatically prescribe the treatment for everyone who tests positive for the virus. Instead, they will usually use a constellation of indicators (age, virus genotype, liver biopsy results) before recommendation.

While pharmaceutical companies smell big bucks in a possible cure for an estimated 170 million folks worldwide, don't look for one tomorrow. Or the day after, for that matter. The problem is that the virus continually changes form when it is attacked by the antibodies, escaping to return again to reside in the liver.

Alt.health

HEPATITIS C HAS proven to be fertile ground for alternative medicine, but don't bother asking your typical HMO doctor about that. I have yet to find a "conventional" doc who does not react to my questions about acupuncture and herbs as if I'd asked about consulting with the closest witch doctor. They chuckle good-naturedly about the "placebo effect."

"The medical establishment is defensive," bestselling author Andrew Weil, M.D., assures me, "because they know their own treatment methods are so poor."

Weil, whose common-sense approach to holistic health has sold millions of copies of Spontaneous Healing and 8 Weeks to Optimum Health, speaks for many alternative practitioners when he weighs the benefits of the two approaches.

"I think there's a great deal available in Eastern medicine," says Weil, reached by phone at his office in New York. He also says he thinks that doctors tend to hit the panic button too soon.

"While [hepatitis C] is potentially a serious disease," Weil says, "I think there's a lot of alarmism. A lot of people are told they're headed for a liver transplant, and that's wrong."

Weil adds that the medical profession is aided by some media coverage that is "extremely alarmist and scary.

"People's awareness about it needs to be raised, but people don't need to be panicked."

Weil has a point. What media coverage there is tends to overlook one very good piece of news: New rates of HCV infection have dropped to one-sixth of the pre-1990s numbers. Thanks to blood donor screenings and needle-

Death from complications of hepatitis C is agonizingly slow. As cirrhosis moves into its final stages, the liver can no longer detoxify, and detritus travels up and settles in the brain. What begins as inattention soon moves into full-blown delirium. The skin and eyeballs develop a ghoulish green-orange tinge from the toxins. Blood cannot get through the strangled capillaries and veins of the liver, and begins backing up. Maybe into the abdomen, which swells up like a basketball. Or into the esophagus, which leaves its owner vomiting blood. As far as ugly ways to die go, liver disease rates right up there.

Fortunately, some high-profile folks have found the energy to speak up and raise public awareness.

There's country music star Naomi Judd, honorary spokesperson for the American Liver Foundation. Judd, who believes she contracted HCV through an accidental needle stick while working as a nurse, helped bring hepatitis C out of The New Yorker and down to the masses. National Enquirer and Star headlines frequently reported on the Songbird's Courageous Battle with Deadly Disease. Judd was one of the lucky ones; she reports testing negative for HCV since undergoing interferon treatment.

Liver Let Die

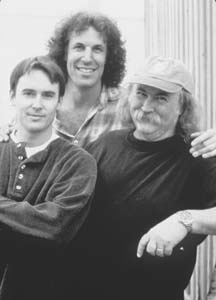

WHILE JUDD GAVE hepatitis C its "innocent" victim profile, many of us could better relate to '60s songbird David Crosby, who underwent a liver transplant in 1994.

"I was dying," Crosby says simply, calling from a car phone somewhere in Southern California. Best known for his work with Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young, David Crosby developed a reputation for his hard-partying ways in the '60s and '70s. He sobered up in the '80s, but the virus had already found a home. However, Crosby did not know he had hepatitis C until he was in end-stage liver failure.

He was one of the lucky ones. There are approximately 14,000 folks waiting for a liver transplant, but fewer than 5,000 found an available one last year. And all the gold records and limos won't move you to the top of the list--everyone gets to wait in line. Insurance is helpful, though. A new liver will set you back about $300,000. Nor does a new liver "cure" hepatitis C, but it can buy its new owner some time. Crosby counts his blessings for his new life.

As with his drug abuse and eventual sobriety, David Crosby feels compelled to speak up about his bout with the virus and to educate others.

"My interest is in communicating to others the degree that it's out there," Crosby says. "People need to know that it's out there."

While he agrees that some people may be afraid of the stigma attached, Crosby also observes, "I don't see much shame. Most people got it through no fault of their own. We're still not sure how it's transmitted."

Although both Crosby and I have little doubt where we picked up the virus, we are only one face of the disease.

"Hepatitis C is an equal-opportunity employer," Crosby says. "People I encounter who have it cover the whole spectrum."

Crosby is also a success story. Fully recovered, sporting a clean new liver, he has just finished touring with one of his bands, CPR, and begins the "CSNY2K" tour in January with Steve Stills, Graham Nash and Neil Young. He is also finishing up a book on musicians and activism titled Stand and Be Counted and is raising his 4-year-old son.

Another famous sideshow of the '60s was Ken Kesey's Merry Pranksters, a loose-knit crew whose adventures were chronicled by writer Tom Wolfe in the 1968 book The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. While most of the Pranksters have faded into obscurity, Steven "Zonker" Lambrecht found himself immortalized as one of cartoonist Garry Trudeau's most endearing Doonesbury characters. But the real Zonker died last year of hepatitis C. His widow, Candace Lambrecht, agrees that although she knows "tons" of people with hepatitis C, relatively few talk openly about it. For one thing, there's the very real discrimination that happens to those with any chronic disease.

"Hepatitis C is still somewhat mysterious," Lambrecht observes. "You don't even want to bring it up with lovers, potential employers--not to mention the world at large."

One friend of mine who has been married 20 years found out his wife would no longer sleep with him when he was diagnosed with hepatitis C. Forget about getting insurance. And online support groups for HCV caution each other to avoid ever mentioning this disease in the workplace.

But Lambrecht has another theory about why people don't spend much time talking about it.

"I think that most enlightened people do all they can to get away from self-absorption," Lambrecht says. "It's not about denial, but it's debilitating to talk about your disease."

While fascination with one's own health--or lack of it--is as tiresome to others as it always was, it has not slowed a slew of talk shows about everything from bulimia to crappy childhoods to toe fungus, I suppose. But then we got older and real life--and real tragedies--began to happen, sapping the energy from the goblins that once haunted us.

My friend Kimberly has lived through rape, mental illness, divorce, cancer and a parent's recently diagnosed terminal illness in the past eight years.

"If I'd known all this was going to happen," she wisecracks, "I wouldn't have wasted my drama queen act on all the petty bullshit."

In my own case, spoonfeeding my mother and changing her diapers every day until her recent death took up more space in my schedule than worrying about the what-ifs of the 80-20 equation.

I'm willing to chalk part of that up to denial--I feel too damn good to worry about the ol' silent killer. But on the other hand, I can't help but think of this particular problem as an act of Grace. In the range of chronic, life-threatening diseases, it's just my humble opinion that the gods were extraordinarily merciful when they dealt this one to me. I'd like to believe that they considered the vanity factor and spared me Tourette's and the ALS that physicist Stephen Hawking has.

If I end up on ventilators and tubes, all swollen and yellow like a big human basketball, then I fully intend to leave the courageous battling of deadly diseases to the songbirds of this world. Me, I'm gonna whine and mope and do backstrokes in my own little ocean of self-pity. And everyone will be forced to listen because I'm going to die and it's the least they can do for me. (Yes, I've thought a lot about this.)

But that is for later--if ever. For now the specter of illness merely fine tunes today's priorities. With a visible period at the end of the sentence, the pressure's on to clean up one's act before the next great adventure, be it reincarnation or Heaven.

And for the rest of you? You're welcome to share that attitude, of course. But there's something more concrete you can also do, suggests David Crosby.

"Get tested."

And if you're negative for hepatitis C? Crosby has one other suggestion that would be helpful for the priests, songbirds, junkies and sinners of this world:

"Register to be an organ donor."

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © 1999 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

![]()

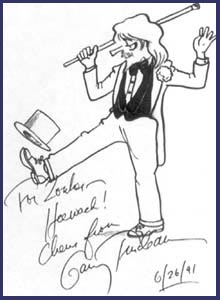

Hep Cats: This artwork was given by Garry Trudeau to 'Zonker' inspiration Steven Lambrecht, a hepatitis C sufferer, who raised a family in San Jose. The original Zonker character was from Tom Wolfe's book 'The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.'

Hep Cats: This artwork was given by Garry Trudeau to 'Zonker' inspiration Steven Lambrecht, a hepatitis C sufferer, who raised a family in San Jose. The original Zonker character was from Tom Wolfe's book 'The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test.'

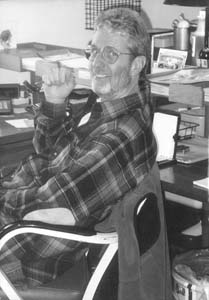

Celebrity Cs: One-time Merry Prankster and San Jose chemical engineer Steve Lambrecht, the inspiration for Garry Trudeau's 'Zonker' character, died of hepatitis C in 1998.

Celebrity Cs: One-time Merry Prankster and San Jose chemical engineer Steve Lambrecht, the inspiration for Garry Trudeau's 'Zonker' character, died of hepatitis C in 1998.

Celebrity Cs: Country music star Naomi Judd, who believes she contracted hepatitis C through an accidental needle stick while working as a nurse, has recovered through interferon treatments and become the honorary spokesperson for the American Liver Foundation.

Celebrity Cs: Country music star Naomi Judd, who believes she contracted hepatitis C through an accidental needle stick while working as a nurse, has recovered through interferon treatments and become the honorary spokesperson for the American Liver Foundation.

exchange programs, new infections of HCV for 1996 numbered 36,000, compared to an average of 230,000 new infections a year in the 1980s. But there is also the bad news: Hepatitis C's eventual impact has a balloon effect. About 10,000 of us who have had this virus ticking away for a couple decades will die this year from liver disease. Already, complications from hepatitis C are the leading cause of liver transplants. By 2010, an estimated 38,000 a year will be dying, more than are dying from AIDS.

Celebrity Cs: Sixties songbird and reformed party animal David Crosby (of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young fame) discovered he had hepatitis C when he was in end-stage liver failure. He got a liver transplant in 1994.

Celebrity Cs: Sixties songbird and reformed party animal David Crosby (of Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young fame) discovered he had hepatitis C when he was in end-stage liver failure. He got a liver transplant in 1994.

From the December 2-8, 1999 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.